How Transracial Adoptees Can Explore Identity Through Cultural Foods

One of the everyday struggles of transracial adoptees is finding a comfortable balance in identity between their country of origin and the culture they were adopted into. Of all the countries where international adoption is common, China saw the largest number of children adopted by American families in the 90s and 2000s.

Due to the implementation of China’s infamous One Child Policy in 1980, an estimated 110,000 Chinese children were adopted internationally between the 1980s and the early 2000s. In 2018, the United States Department of State estimated 8,000 Chinese adoptees were placed with American families between 1992 and 2017. Due to a cultural desire for male heirs, a majority of these adoptees were girls.

The life of a Chinese adoptee in America is an incredibly complex situation. There is a significant difference between American and Chinese cultures, which often leads to a game of tug-of-war between the two identities that many transracial adoptees feel.

How Food Influences our Identity

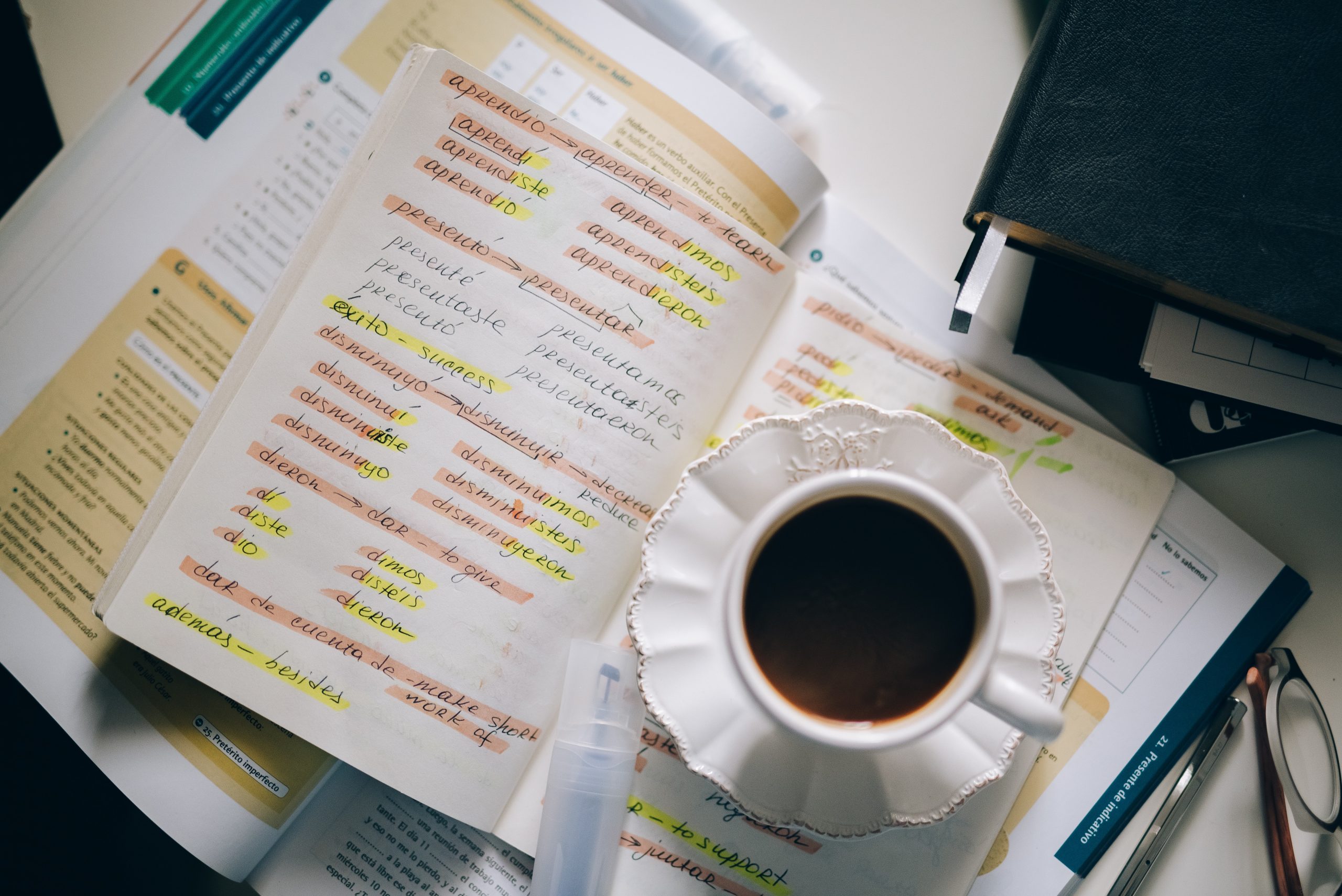

Many aspects of life allow us to maintain a sense of community and identity. Cultural foods are a perfect example, as many dishes are deeply rooted in religion and history.

Many immigrants and individuals traveling abroad for school or work choose to eat foods from their respective cultures. This helps them maintain their sense of identity and connection to their home country. Studies have found that a strong sense of identity strongly correlates with an increase in general well-being, especially in first-generation immigrants.

In the case of Chinese transracial adoptees, there are no memories of homemade xiao long bao, the smell of baozi floating from one street vendor to the next, or the taste of Lunar New Year mooncakes. With the appearance of someone who should know what these foods are and what they taste like but doesn’t, many transracial adoptees wonder if they are “cultured enough.”

Dr. Kim Park Nelson, a Korean adoptee and associate professor of ethnic studies at Winona State University, says, “The most common example I hear, and what I have experienced, is being asked if I like kimchi. I do, but not all adoptees are crazy about kimchi. There is almost a nationalistic connection between kimchi and Korea. It’s like a test question: are you really Korean?”

Exploring Identity Through Food

Food is more than a way to nourish our bodies. With communities as old as those found in certain parts of China (some dating back to 2100 B.C), certain dishes carry centuries of history and culture. People of the same cultures structure their societal classes, celebrate holidays, and adapt to the world around them through food. French social scientist Claude Fischler writes, “Food and cuisine are a quite central component of the sense of collective belonging.”

Many Chinese-American adoptees connect to their home country by learning about and sampling traditional food. From discovering authentic dishes nearby or learning how to cook them at home, trying foods from one’s home country often helps adoptees find a new sense of cultural identity.

Of course, this will never be the same as having grown up in an environment where these foods are eaten regularly. Still, it does help adoptees find a similar sense of community. As author and Korean adoptee Misty Shock Rule puts it, “It’s the fate of an adoptee to continue searching and learning.”

The mental and emotional journey of transracial adoptees is never-ending. It comes in an infinite amount of shapes, sizes, and colors. What works for one adoptee may not work for another, but learning about their culture’s foods may help them discover new aspects of their identity and overall feel more inclusive.