The Cultural Backdrop In Hollywood’s Biggest Films

The Cultural Backdrop explains how some of Hollywood’s biggest films lend themselves to the “cultural background.” This article will be a dissection of the disparity between the storytellers and the culture they borrow to tell the story.

Explaining The Cultural Backdrop

The Cultural Backdrop is when a director sets a film in a country with which its main characters are unfamiliar for the sake of creating an unknown environment for them to journey in.

They use these other countries as devices to improve their characters and stories without caring about the culture they’re borrowing from or the people of colour who seem to serve them silently in the background.

Some films focus on white protagonists who have lost their identities and use other cultures to pull themselves out of their slump. Others simply enjoy using foreign countries for their differences from their home countries.

There is little regard for the actual culture, which is simply a physical reminder that these characters are in a world so vastly different from their own. As the film ends, they leave the country, having taken what they needed from it, and go back to their American lives.

This trope is often used with Asian countries. The Western film industry perceives countries like Japan and Korea as indecipherable. What they cannot understand, they tend to take advantage of.

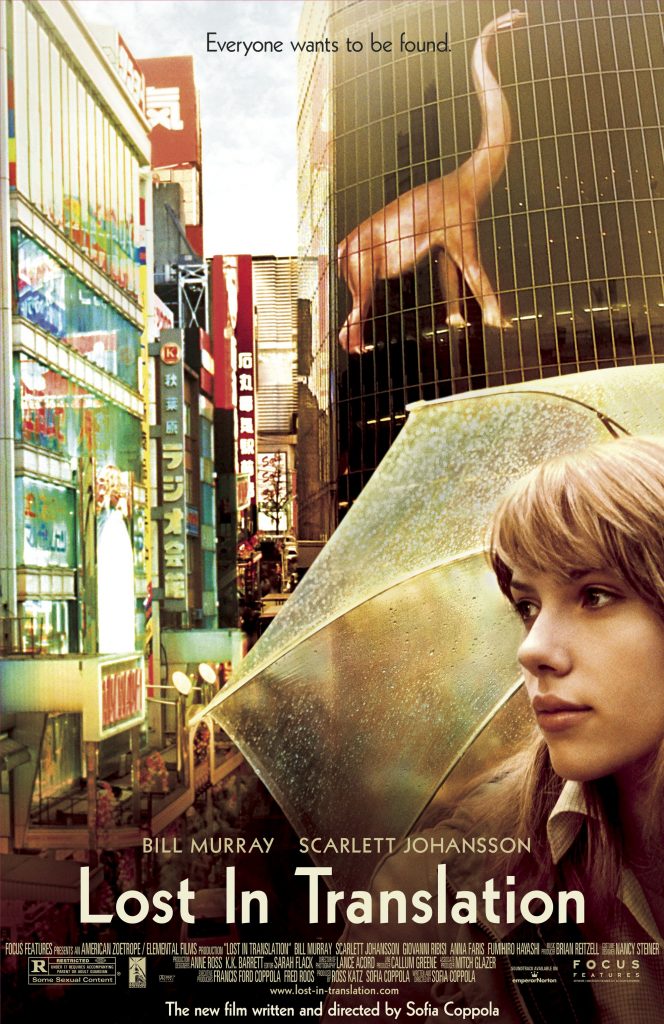

Lost In Translation (2003), written and directed by Sofia Coppola

The film follows Bill Murray and Scarlett Johannson as lost souls in Tokyo; Murray plays a jaded married actor going through a midlife crisis who meets Johannson’s character, a neglected newlywed. While the film’s themes of internal disconnect align with Coppola’s use of a physical foreign destination, Coppola and the characters don’t respect the culture they’re partaking in.

The film is littered with insensitive comments about Japanese people. Murray and Johannson’s characters treat Tokyo as this alien land where nothing they do matters (for example, the mispronunciation/accented English spoken by their Japanese counterparts is often the butt of a joke or a source of discontent). The Japanese characters in the film are mainly used as silent plot devices, uplifting their white counterparts in their own country and giving no genuine contribution other than to fill the background. Although Coppola insists that the film is more of a love letter to Tokyo, there have been accusations of the film’s orientalist approach.

The film is reported to be solely written by Coppola (a white woman) however, much of the pre-production and production crew is of Japanese descent.

Lost In Translation had been nominated for 113 awards and had won 98 including Coppola’s win for Best Original Screenplay in the 2004 Academy Awards.

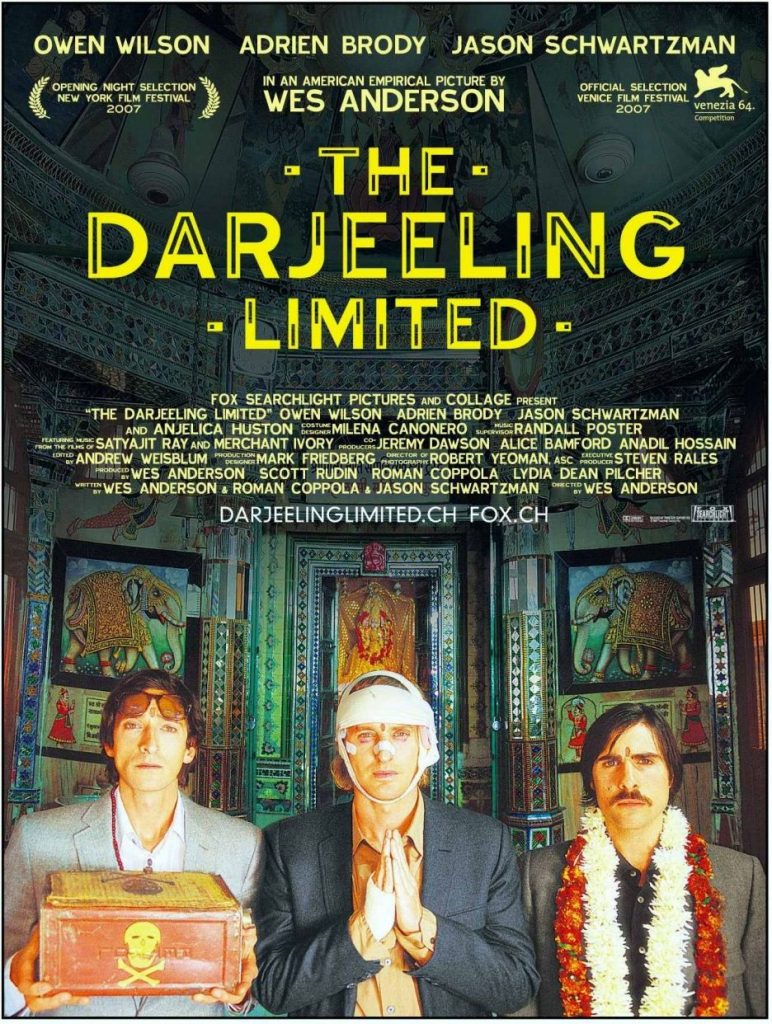

The Darjeeling Limited (2007), written and directed by Wes Anderson

The film follows three brothers’ reunions a year after their father’s funeral. Anderson’s film uses the Cultural Backdrop concept just as Lost In Translation does. The brothers traverse India, indulging themselves while combatting their own issues. The culture is reduced only to what the brothers need for their journey and plays hands at orientalism and passive jokes.

Women of colour are treated as stereotypical sensual objects for their white counterparts (in this case, as Jason Schwartzman’s first distraction from the end of his on-and-off again relationship with Natalie Portman). The Indian characters in the film are simply there to be saved by or slightly derail the plans of Schwartzman and his brothers.

In an early scene, Owen Wilson’s character says, “We didn’t know, we’re just trying to experience something. It’s very important to us,” to the Chief Steward, played by Waris Ahluwalia. He says this in defence of himself and his brothers for bringing a poisonous snake onto Ahluwalia’s train that rides throughout the Indian countryside. Without any regard for the country they are in and solely focusing on their spiritual journey, Wilson and his brothers do what they deem as innocent but are actually harmful.

While the film does a beautiful job at capturing the depths of strained familial relationships and the loss of self-identity, it does so at the cost of writing an idyllic, stereotypical India.

The script was entirely written by Wes Anderson, Roman Coppola, and Jason Schwartzman. There were no people of colour in the writing process, although there was a considerable amount in the pre-production crew.

How To Break The Stereotypes

People can write what they please and shoot films where they want. However, the industry is changing and so must the processes behind films regarding various cultures. Countries and cultures should not be reduced to what their white counterparts can easily digest. The only way to write from an outside point of view (or even within a point of view) while maintaining sensitivity is to consult people who are part of those cultures.

There is no lack of films about white people and cultural displacement, but there is a lack of people of colour in the writing rooms. The only way for films to be made respectfully for all audiences is to have more diversity within their crews.