Horror Under a Looking Glass: An Comprehensive Comparison of Rosemary’s Baby (1968) and The Invisible Man (2020)

Even on the big screen, can it still be all in your head? There are various sub-themes and tropes within the horror genre, which revolve around social identity characteristics such as race and gender. Perhaps one of the most well-known is that of the “crazy” girl that no one believes, often to their detriment, as they eventually end up face-to-face with the very monster they’ve claimed is “only in your head”. Not only is the character popular enough to become a horror movie trope, but she has been featured in some of the best-known films, such as Rosemary’s Baby (1968) and The Invisible Man (2020), a character that gives an in-depth look at the horrific treatment of women at the hands of an uncaring, and even malicious patriarchy.

What Is the Inclusion Criteria?

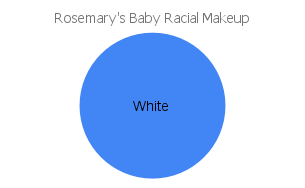

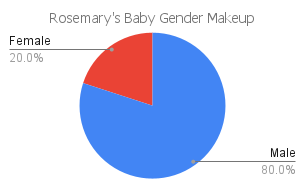

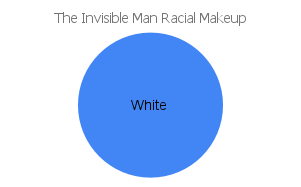

The films were selected from RottenTomatoes Top 100 Horror Movies page. Once selected, the diversity statistics of the films were analyzed, primarily in terms of the distribution of film leadership roles. The cast/crew roles included in the data analyses include director, writer, lead actors, producers, and executive producers. The data was also formatted into the racial categories of White, Black, Hispanic, Asian, and Middle Eastern, and the gender categories of Male and Female. This was all sorted into two separate pie charts for each movie.

How Inclusive Is Rosemary’s Baby?

Rosemary’s Baby (1968) drew a 96% rating from critics and an 87% rating from viewers on Rotten Tomatoes. Within its leadership, 100% of the cast/crew roles of the film were occupied by White members. In its gender diversity, 20% of the cast/crew was made up of female members, with a remaining 80% of male members.

The film starts just like any other: a young couple moves to a new apartment building in the hustle-and-bustle of New York City. Rosemary and her struggling actor husband Guy meet their neighbors, elderly couple Roman and Minnie, who welcome them with open arms. But over time, Rosemary senses the eerie feel of her new situation, which only grows with her pregnancy and the odd interest the neighbors have taken to it. As she struggles with her sanity, unsure of whether to believe in the existence of demonic evil, she draws closer and closer to the truth about her baby: Rosemary carries the spawn of Satan, thanks to her conspiring neighbors and husband. The film ends with this discovery and Rosemary’s acceptance of her situation as the devil’s mother.

How Can We Analyze The Film?

There are many points of analysis of the film, especially due to its female protagonist as a feature film made in 1968. The fear of pregnancy and children, especially how they will end up, rings throughout the entire movie; what better way to exhibit these fears than to make the devil the source of both? But another message comes through the film, which centers itself not on the fears of other things, but those which come from women: the fears of existing within a female body. The “condition” of being female is the perspective shown through Rosemary’s eyes; it is her helplessness in the face of her husband, her neighbors, and the plan that they have for her that freezes the audience in terror. The invasion of her body, in both rape and pregnancy, gives a living, breathing quality to the fear that comes with men making decisions about women’s bodies behind their backs; it gives the audience the experience of being treated as less than human and for that, it remains one of the greatest horror movies ever.

But there is only so much weight that this message can take on with its leadership diversity; as represented in the statistics above, the only woman involved is lead actress Mia Farrow. Aside from the source material written by another man, Ira Levin, it is even more disturbing to hear that Roman Polanski, a statutory rapist, was the director of what is now considered a feminist film. With this baggage, there is much to take in with Rosemary’s Baby, for it is more than just a typical Hollywood picture.

How Inclusive Is The Invisible Man?

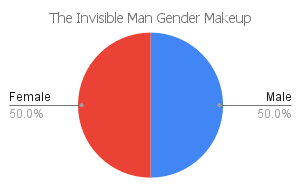

The Invisible Man (2020) drew a 91% rating from critics and an 88% rating from viewers on Rotten Tomatoes. Within its leadership, 100% of the cast/crew roles of the film were occupied by White members. In its gender diversity, 50% of the cast/crew was made up of female members, with a remaining 50% of male members.

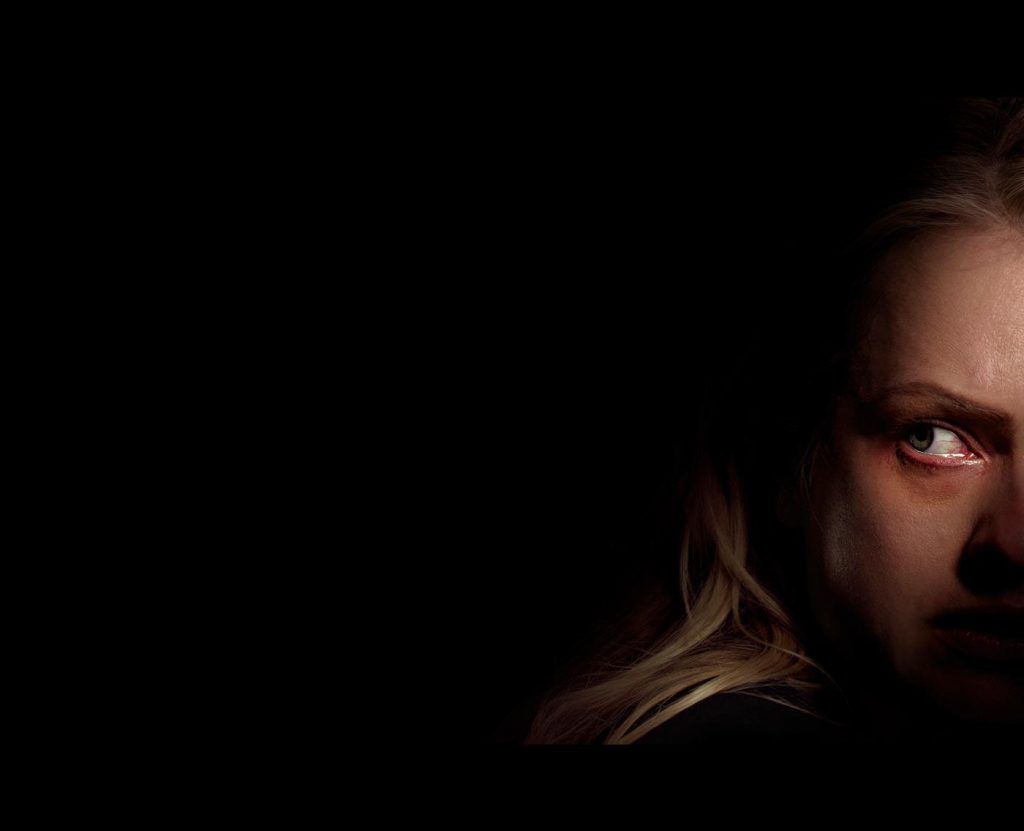

After almost a full century since the original film, the story of the Invisible Man was reinvented into another cinematic narrative of the same name. The Invisible Man follows Cecilia Kass as she navigates the almost hidden horrors that follow her: first an abusive relationship, then the terrorizing pursuit of her ex-boyfriend, also known as the Invisible Man. After staging his suicide, ex-boyfriend Adrian Griffin uses his newfound invisibility powers to go after Cecilia, whom no one believes about any of it. Left to face him alone, she decides to fight back instead of living in fear again.

How Can We Analyze The Film?

Though the original story exists based on science fiction, with an invisibility potion the ignition key to the rest of the events, the nature of the 2020 film is anything but fictional. Though the movie alludes to an advanced technology that gives the abusive ex-boyfriend the ability to remain hidden as he terrorizes ex-girlfriend Cecilia, the basis of the terror itself is rooted in the privilege of men and their abuse of such privilege. Just as Adrian Griffin remains invisible to others as he seeks his revenge on Cecilia, abusive men are often not just alive but thrive in society with none of the consequences for the violence they have committed. In that sense, they are invisible to everyone; privilege endows them with an absence of scrutiny, no matter the clues telling otherwise.

The message present within The Invisible Man rings stronger with the background cast and crew of the film; with a 50% cast/crew of women, it is made evident that the story told has been passed down through women’s hands, shaped and sculpted with their insights. This gives the narrative surrounding not just relationship abuse but the gaslighting that follows greater substance; with women being the majority of victims, these perspectives give truth to the story told and the horrors that rage on inside of it.

What Can We Conclude?

There are many words for films like Rosemary’s Baby and The Invisible Man, ranging from impactful, shocking, and the most utilized, simply “feminist”. But these films, even with their representation of female protagonists and their trials and tribulations, fall within the ever-encompassing progressive nature of the horror genre. It seems that only horror, with its use of the universality of fear, can make entire audiences see what others live through and die from.