Adoptees Don’t Need to be Saved, Even In Hollywood Films

There are hundreds of books and films with plots focused on adoption and the complex and heartwarming stories of adopted families. While most people love a feel-good film, it is easy to neglect the importance of focusing on the adoptee rather than their family.

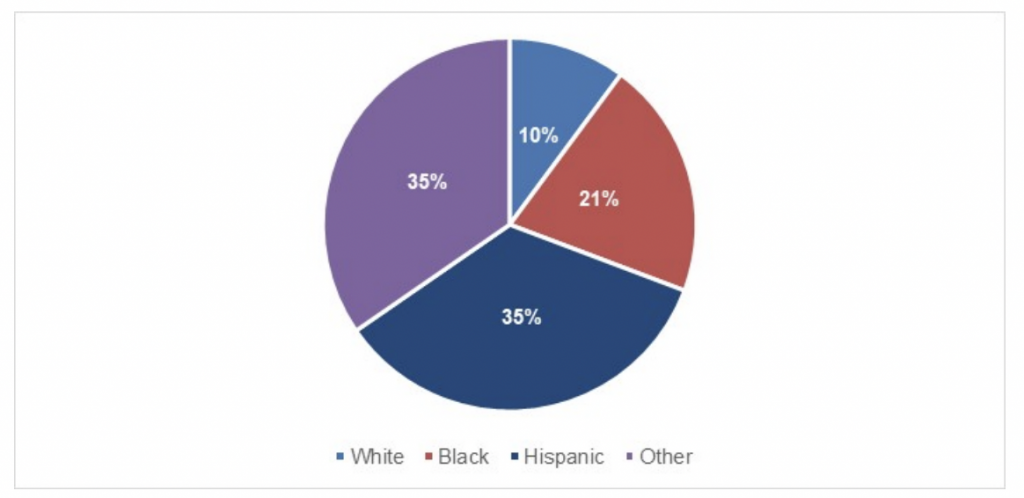

As with societal attitudes towards adoption, mainly when a white family adopts a child of color, adoptees are often labeled as the “good deeds” that their families did and because a white family has adopted a child of color, that in itself automatically makes them good people. This way of thinking is problematic for many reasons: it romanticizes transracial adoption, puts white adoptive parents on a pedestal they should not be on, and diminishes the space meant for the adoptee to come to terms with their adoption story. According to the US Department of Health and Human Services, only about 10% of US adoptees from 2017 – 2019 were white.

White saviorism is the belief that white people, historically the race with the most privilege and power, can “save” members of other races by “helping” rather than learning about the history behind systemic racism and working with others to help end it. It is easier for people to try and ignore or overwrite the wrongs of the past than apologize and learn from them.

Adoption Saviorism in The Blind Side (2009)

The Blind Side (Hancock, 2009) tells the story of Michael Oher (Quinton Aaron), a high school football player who overcame homelessness to become a star athlete thanks to the love and support from his newfound adoptive family. While this seems like a perfectly lighthearted plot, a darker undertone makes itself apparent when looking through a racial lens.

The Blind Side was based on Oher’s biography, The Blind Side: the Evolution of a Game, published two years before the film’s release. While the core story remains the same, many subtle differences between the film and the biography are problematic. One was written by a black man and the other by a white man, and that difference alone creates two entirely different demeanors.

The Blind Side focuses more on the story of Leigh Anne Tuohy, Oher’s adoptive mother. Oher is a black homeless teenager who has been out of the school system for years and is taken in by Tuohy and her husband. With their help, he becomes a star football player for a local high school team, successfully graduates from school, and receives a scholarship to play as a college student. While this is a heartwarming and insightful angle, the film creates a story in which Oher is “fixed” by his white adoptive mother as she teaches him how to play football and guides him to a football scholarship for her alma mater.

Negative Effects of The Blind Side (2009)

In an interview, Hancock said of finding his inspiration for the film, “After I had read the book, I realized that while sports are a major part of the story, there is also a very unconventional mother-son relationship. I was intrigued by this strong woman character. This mother took in a boy she didn’t even know.” The “othering” of adoptee stories is hugely isolating to the adoptee community. It creates an unnecessary divide between the adoptee and their adoptive family.

Oher himself admitted in an interview with ESPN that he actually did not approve of the film due to its negative effects on his football career. He believes that the fame of the film has colored people’s perception of him and rather than seeing him as a valuable member of the Carolina Panthers, they see him as the young boy saved by a charitable white family. In the interview he said, “That’s taken away from my football. That’s why people criticize me. That’s why people look at me every single play. I’m tired of the movie. I’m here to play football”.

Combating Saviorism in Adoptee Films

First and foremost, listening to adoptees, their stories, and their feelings is essential. Only by listening can we begin to understand people who are different from us. Learning about a new group of people is like learning other crucial things in that it takes research, dedication, and time. For many people, this understanding also requires acknowledging the damage they or their communities have done to others (ex: white people historically damaging minority communities).

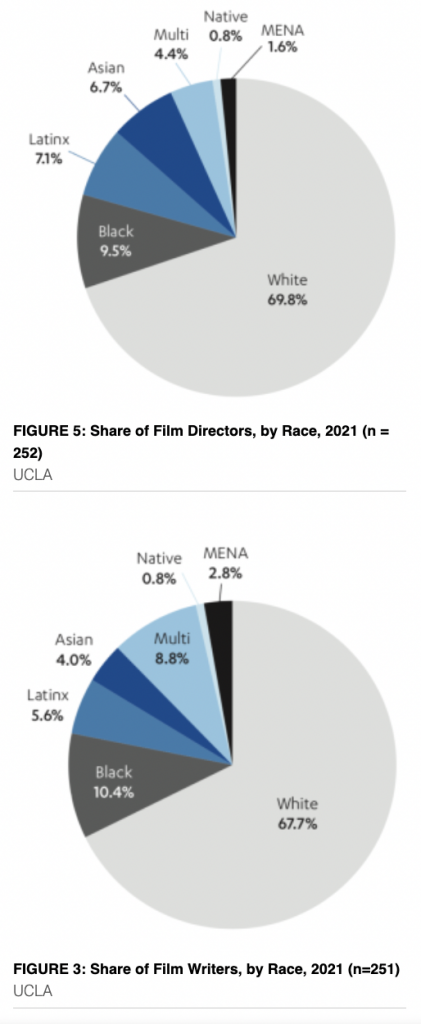

When writing, casting for, and producing films with stories involving adoptees (especially adoptees of color), people of that community must be as involved with production as possible. Not only will this help the film take on a more informed voice, but it will also provide people of color with opportunities to tell their own stories. A UCLA study found that about 69.8% of film directors in 2021 were white, and the remaining 30.2% were all other races, revealing a significant yet unsurprising trend.

Filmmakers and moviegoers should make an effort to be more informed about where the inspiration for adoptee-focused films comes from and how many adoptees are/ were involved in the film’s creation. Particularly in telling stories of adoptees of color who white families adopt, one must also be mindful of racial biases.